On a main street in Hanoi, the restaurant announced itself through scent and sound—it reeked of cheap distilled rice liquor and was filled with the percussive laughter and coarse curses coming from men who had gathered to perform a particular kind of Vietnamese masculinity.

Unlike lechon, you would not see the whole roasted dog on display, though no one would have considered it ostentatious had one been there. Without the faded sign, weathered to almost illegibility, that simply reads, Dog Meat, an unfamiliar passerby might get confused about what exactly the place was selling.

When I was eight, walking to and from grade school each day, I would pass by this restaurant.

My mother was terrified of dog meat, of how people could possibly bring themselves to eat such an endearing animal. My father, a Western-educated man, in contrast, was once a fan of the meat. He didn’t eat it daily, like some, but whenever he did, he would tell my little sister and me about how good it was.

My father has done many things wrong; eating dog meat was never one of them. My mother has done many things right; refusing to eat dog meat is not, morally speaking, her greatest triumph.

No country but China consumes more dog meat than Vietnam, where an estimated five million dogs are eaten every year.

Whether that number is shocking depends on who you ask.

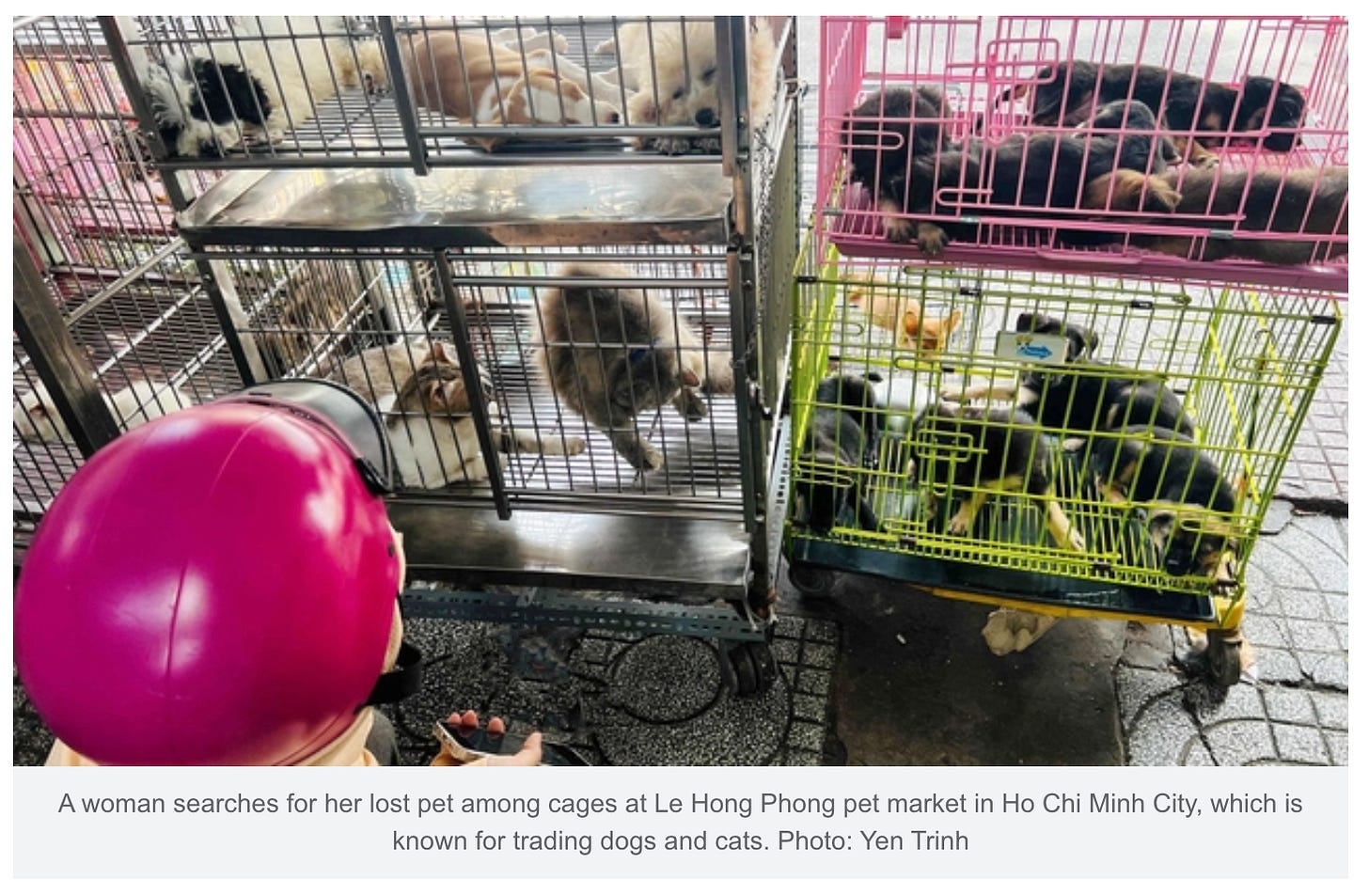

To me, it’s utterly horrendous. Images of dogs writhing under electrical torture, their carcasses dragged on the street as the thieves flee the scene, while living ones are crammed into rust-stained cages, transported to slaughterhouses in appalling conditions, haunt me every time I see them.

Vietnamese men eat dog meat for patriarchal reasons. Beyond the universal association between red meat and masculine identity, Vietnamese culture has constructed an intricate mythology around canine consumption: combined with alcohol, the meat allegedly amplifies strength, assertiveness, and sexual prowess, a form of sexual aphrodisiac.

Anthropologist Nir Avieli's fieldwork in Hoi An reveals an even more elaborate cultural architecture underlying this practice. In Vietnam's Confucius society, where public masculinity demands not merely performance but active engagement in social and political spheres, dog meat restaurants become theaters of belonging. Furthermore, as Avieli documents, "In Hoi An, dog meat is less about culinary preference and more about political loyalty: those who ate it did so to demonstrate allegiance to the northern regime." Dog meat, traditionally a Northern dish, transcends appetite, becoming a form of embodied politics, an ironic expression of cosmopolitanism and modernity.

In Vietnamese cities, there exists a particular type of street that desperate pet owners visit first when they realize that their pets have disappeared—black markets where stolen dogs are traded. The existence of sites like these illuminates a grim reality of Vietnam’s dog meat industry, one that feeds not only on these highly affectionate animals but also on the inconceivable pain of families whose dogs are stolen from them.

My greatest objection to Vietnam's dog meat consumption lies not in the species being consumed but in the willful blindness to others’ psychological suffering, the casual acceptance that one's meal might be someone's stolen family member.

Years of poverty and a survival-driven mentality have driven the Vietnamese psyche toward the readily available, the short-term, and the immediately beneficial. This is the same population that, within the last 100 years, has experienced famines, plural: the 1945 famine, when Japanese forces requisitioned rice fields for cotton and jute to feed their war machine, leaving two million dead, and the near-starvation of three million more in the 1980s, when centralized planning in Northern Vietnam failed.

In such contexts, extending moral consideration to animals beyond the immediate necessity for survival was a luxury people simply could not afford.

Recently, Vietnamese social media erupted over a proposed six-year prison sentence for a man who illegally acquired a silver pheasant, an endangered bird, successfully bred ten, then sold them for profit. Netizens rallied to his defense, arguing he deserved praise, not imprisonment, for breeding an endangered species. Conservation experts had to explain the crucial distinction between economic breeding and conservation: captive breeding often renders animals unable to survive in their natural habitat, defeating conservation's purpose entirely.

This is rooted in a strikingly similar mentality, one that fails to look beyond the immediate consequences of one’s actions. It’s the same as squeezing into any open gap in traffic until the whole intersection is blocked; the same as cutting in line until everyone waits longer in disorder; the same as dumping trash into the river until, in the end, they drink the water they polluted.

The Vietnamese mentality is neither communal nor collective: it’s individualistic, not in the liberal sense of rights and identities, but in terms of greed and self-interest.

I do not mind Vietnam being called a “dog-eating country.” It’s just descriptive. The consumption itself, while repugnant to me, is no more ethically problematic than my own consumption of pork—after all, pigs are no less intelligent than dogs.

What troubles me profoundly is the illegal capture, the systematic torture, the psychological agony inflicted on families whose pets vanish into this shadowy industry, and, most importantly, the ignorance of people who overlook such ramification.

The practice, however, is waning. My dad and many men of his generation have stopped eating dog meat. Restaurants are closing, and younger people are disapproving. The market economy is doing its thing, running once crowded parlors out of businesses as people steer away from the meat.

My argument against the consumption of dog meat is more emotional than logical.

I don’t believe in superstitions, in the karmic punishments people say befall former dog meat restaurant owners, but I believe in the power of the heart in making these social and behavioral arguments: if you cannot find a reason to show compassion for creatures so close to humans, or consideration for fellow humans who regard these animals as family, what exactly do you stand for?

I hope there comes a day when we Vietnamese realize that we need a revamp in mentality. When, or if, the day comes, I hope it begins not with ideology or politics, but with the heart, with compassion and empathy.

I really enjoyed reading your thoughts!

SUCH a great write up and nuanced discussion. I've been met too many times with "dont your people eat dog meat?" when they found out I'm viet and I never knew how to appropriately respond that covered my personal views (against eating dog meat) while also showcasing a non westernized view of how a different culture has evolved to such practices